Building resilience in the face of deluge: Rethinking infrastructure in flood-prone Himachal Pradesh

by Tejasvi Sharma, Chief Editor, EPC World

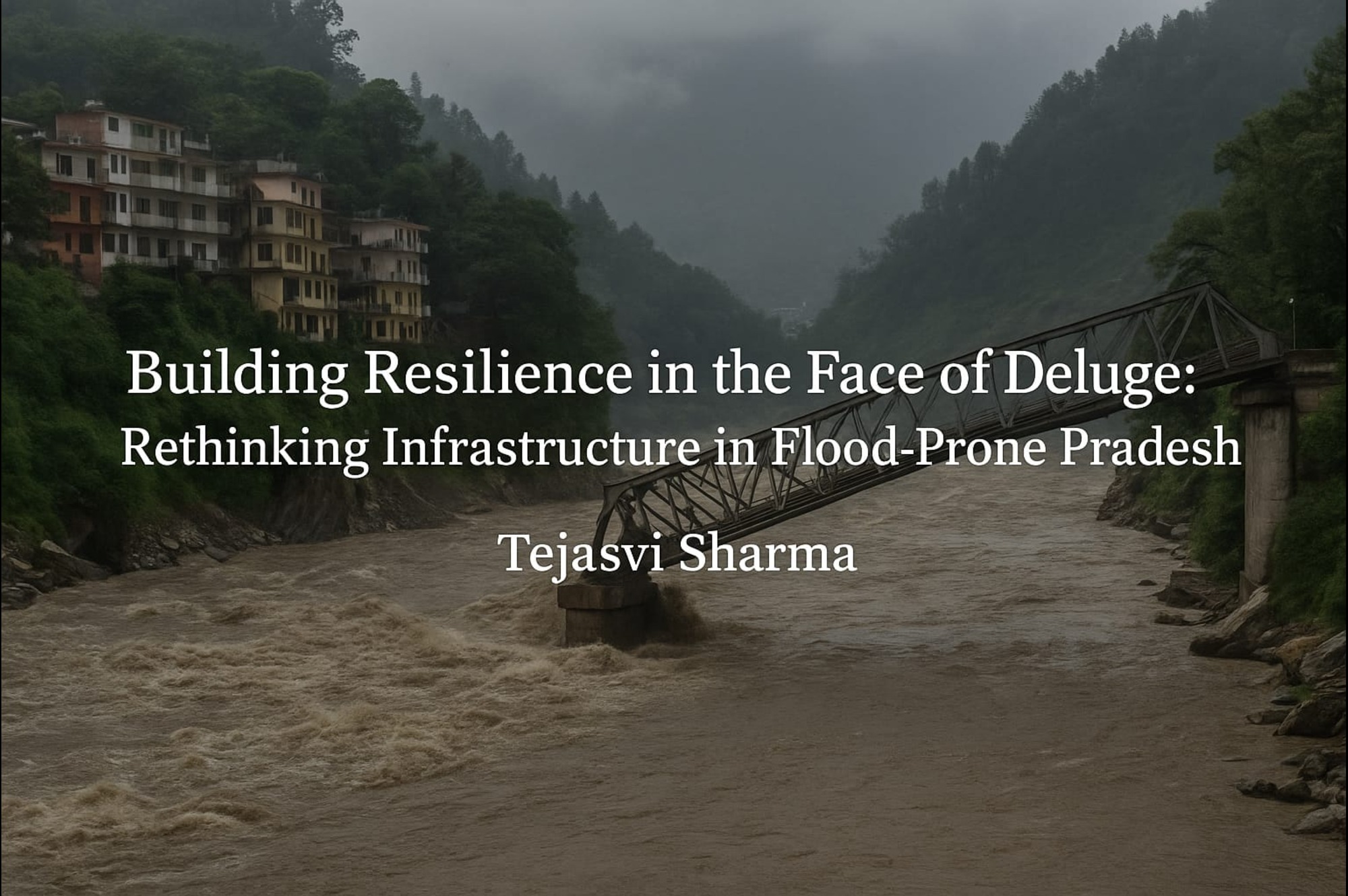

In the verdant hills and sweeping valleys of Himachal Pradesh, a paradox confronts policymakers and engineers alike. For decades, the state has lured tourists with its unspoilt landscapes while simultaneously witnessing a creeping vulnerability to catastrophic flooding. In 2025, this vulnerability was laid bare yet again as relentless monsoon rains battered the state with unprecedented fury. Official records confirm that nearly 95 lives have already been lost, with 33 people still missing, and over 250 roads remain impassable. While floods are hardly novel in the Himalayas, the sheer frequency and magnitude of destruction are intensifying, demanding a reckoning with our technologies, planning paradigms, and regulatory frameworks.

The present status: A sobering assessment of flood damage

As of July 2025, infrastructure losses in Himachal Pradesh are estimated between ₹541 crore and ₹752 crore, according to the state’s Disaster Management Authority. This figure accounts only for public infrastructure: highways, bridges, water-supply systems, and power transformers. If the destruction of private dwellings, agricultural lands, and tourism facilities is included, the total economic loss will almost certainly exceed ₹1,000 crore. Districts like Mandi and Kullu have borne the brunt of devastation. Mandi alone reported over 180 blocked roads, with arterial highways rendered unusable by landslides and subsidence. Power and water infrastructure has also suffered crippling damage, with 787 water-supply schemes and 327 transformers disrupted as torrents of debris swept across settlements.

Technological gaps: What are we missing?

Despite considerable advances in civil engineering, critical technologies that could mitigate such disasters remain grossly underutilised:

1. Integrated Early Warning Systems

While the India Meteorological Department issues general rainfall advisories, real-time flood forecasting tailored to Himachal’s micro-watersheds remains patchy. Many river basins still lack telemetry-enabled gauge stations capable of providing actionable alerts.

2. Resilient Bridge and Road Design

Modern bridge engineering offers modular pre-stressed spans designed with rigorous hydraulic and seismic considerations. Yet many bridges still rely on outdated load models, shallow foundations, and minimal scour protection—rendering them highly vulnerable.

3. Bioengineering Solutions for Slopes

Techniques such as reinforced earth walls, geocells, and vegetative stabilisation of embankments can dramatically reduce landslide risk. However, adoption remains sporadic, limited by both funding and the inertia of conventional civil works departments.

4. Permeable Urban Surfaces and Floodplain Restoration

Towns such as Kullu and Mandi have rapidly concretised floodplains, increasing runoff velocities. Technologies like permeable pavements, rain gardens, and riparian buffer restoration are almost entirely absent from municipal planning.

Strategic planning: What needs to change?

Infrastructure planning in Himachal Pradesh has historically prioritised connectivity and revenue generation over resilience. This paradigm must shift decisively:

a) Watershed-based master planning

Investments must be conceptualised at the catchment scale, taking cumulative hydrological impacts into account rather than rubber-stamping piecemeal approvals.

b) Mandatory climate risk assessments

Every highway, bridge, or urban expansion project must undergo rigorous climate vulnerability assessments. Funding should be contingent on demonstrable mitigation measures.

c) Retrofitting existing infrastructure

Rather than allocating disproportionate funds to new roads, the government must prioritise retrofitting vulnerable bridges with deeper pile foundations, improved scour protection, and flood-resilient substructures.

d) Disaster-resilient settlements

Relocating the most exposed settlements and providing incentives for elevated and reinforced housing designs is no longer optional but a moral imperative.

e) Legislative reforms: Overhauling building laws

The Himachal Pradesh Town and Country Planning Act and associated building bye-laws are overdue for comprehensive revision:

f) Elevation mandates

For all new construction in designated flood zones, plinth levels must be raised at least 1.5 metres above the highest recorded flood level of the last 100 years.

g) Material standards

Building codes must mandate flood-resistant materials: waterproof concrete additives, corrosion-resistant reinforcements, and protective membranes.

h) Slope stability norms

For slopes steeper than 30 degrees, detailed geo-technical assessments, drainage controls, and engineered retaining structures must be compulsory.

i) Strict enforcement and penalties

Many collapsed structures this year were unauthorised or deviated from approved plans. Enforcement must be strengthened, with exemplary penalties and mandatory demolition of illegal builds.

The Economic Toll: Counting the cost

The economic toll is staggering. Even in 2023, monsoon floods inflicted over ₹10,000 crore in damage. This year, though the numbers are still evolving, the state has already crossed ₹700 crore in public infrastructure losses by mid-July—a figure almost certain to climb further as assessments continue. The indirect losses, including disruption to tourism and agricultural output, could double this figure over the next 12 months. If the pattern holds, the cumulative damage over the decade may eclipse ₹25,000 crore, an unsustainable burden for any Himalayan state.

Flood Mitigation: Controlling the Deluge

While no intervention can fully neutralise flood risk in such a fragile ecosystem, a multi-pronged strategy can dramatically reduce losses:

1. Afforestation and Catchment Treatment

Dense vegetation slows runoff, stabilises slopes, and reduces sedimentation. Programmes like Ridge to Valley treatment must be massively scaled up.

2. Floodplain Zoning and Enforcement

Strict no-build zones within 50 metres of riverbanks must be enforced without exception, using satellite monitoring to curb encroachment.

3. Reservoir Regulation and Sluice Management

Hydroelectric dams must adopt dynamic flood management protocols, balancing power generation with timely discharge to avoid catastrophic breaches.

4. Community-Based Disaster Preparedness

Local residents must be trained in evacuation, first aid, and early warning reception—transforming passive victims into informed first responders.

Conclusion: The Imperative of Resilience

Himachal Pradesh stands at a crossroads. The promise of prosperity through infrastructure and tourism is undeniable. But so too is the peril of amplifying vulnerability through outdated standards and complacent planning. If this year’s floods have taught us anything, it is that incremental neglect becomes cumulative catastrophe. The technologies to build better already exist. The knowledge is readily available. What remains is the political will and societal consensus to prioritise resilience over expedience.

Nature, it seems, is delivering the same lesson over and over: the measure of a mature society is not merely its capacity to build but its wisdom to build wisely. Himachal Pradesh—and India—must rise to that standard before the next monsoon makes the cost of inaction intolerable.

Tejasvi Sharma is Editor-in-Chief of EPC World, specialising in infrastructure policy, disaster resilience, and sustainable development.

Tags