Bridging the Energy Divide: Making Clean Energy Accessible & Affordable for Every Indian

Ch. Bhavani Suresh, Founder & MD of Truzon Solar

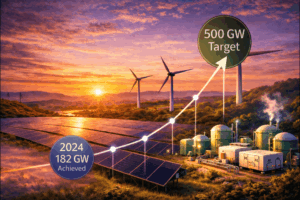

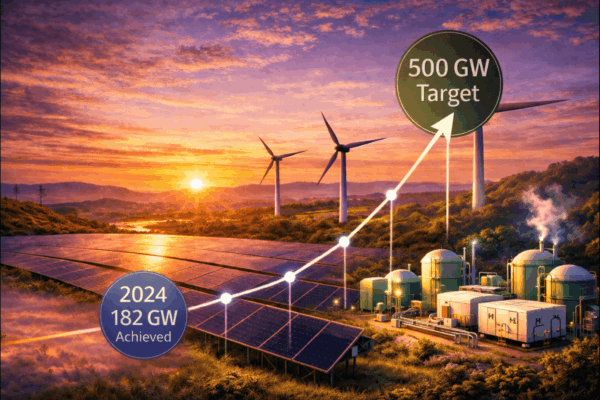

India’s energy provision has historically been focused on ‘megawatts’, through large centralised coal-fired generating plant stations and large-scale solar photo-voltaic (PV) installations in the Thar desert. Generating electricity through the rooftop or the roof of a small producer of goods is an emerging development of equal importance to the development of large-scale renewable energy-generating assets. In addition to the ability to obtain a supply of energy from an electrical grid, the “energy divide” will now also refer to the energy divide between people who have the ability to create, store and control their own energy and those who are dependent on large utilities.

Decentralization: From Megawatts to “My-Watts”

The Centre has made a major shift in how people produce and consume electricity with the announcement of a ₹22,000 crore budget to fund the PM Surya Ghar: Muft Bijli Yojana. With this new program, the government is transforming residents of 1 crore homes into “pro-sumers” by empowering them to become self-sufficient (as opposed to simply consuming) via the provision of renewable energy.

However, the MSME (micro, small and medium enterprises) sector still has a major gap in the renewable energy landscape. There are currently over 90,000 MSMEs across India using conventional electricity sources with many of them continuing to suffer huge financial losses due to high grid electricity tariffs. Solar energy should not be considered an additive “green” technology in places like Surat for textile production and Ludhiana for tool room production, but rather should be thought of as a working capital investment that can significantly reduce the operational costs of these businesses by 20-30% and provide India with the competitive advantages in the global supply chains that we need.

Affordability Beyond Subsidies

The solar revolution was made possible due to government subsidies in its early stages. But by 2026 we expect to see the mature development of a strong, viable domestic ecosystem in the solar industry. Policies such as the Approved List of Models and Manufacturers (ALMM) and the imposition of a Basic Customs Duty (BCD) on imported products have been instrumental in building up a viable domestic manufacturing base for solar panels and their components.

With our “Make in India” initiative to promote the manufacture of solar cells and modules, we will also be able to insulate ourselves from global supply chain disruptions and protect our energy security. In addition, increased economies of scale and improved supply chain integration will lead to lower costs for solar energy solutions than coal, without the benefit of government assistance.

Reliability: Solving the “Sun-Down” Problem

Intermittency has always been the Achilles heel of solar energy, as clean energy will only be economical if it’s produced when there is high demand for electricity, e.g., on cloudy days. Therefore, 2026 will be considered the “Year of Execution” of BESS (Battery Energy Storage Systems).

By integrating storage with solar and utilizing stored energy from noon when excess electricity is generated, and transferring the energy generated and stored to meet peak demand, we have solved the “Sun-Down” problem. As a result, renewable energy has become a 24/7 resource.

Grid Hardening: The “BESS-First” Approach

The national grid of India started reaching its thermal and stability limits as solar capacity exceeded 130 GW by late 2025, meaning that even when the grid has access to energy from solar power, the energy will be useless if the grid trips off the moment a cloud passes over the solar energy park that is providing the energy to the grid.

- Viability Gap Funding (VGF) of ₹1,000 crore for BESS in this year’s budget is a significant development that will improve grid stability.

- All of the major solar Engineering Procurement and Construction (EPC) tenders now include the new “Firm and Dispatchable Renewable Energy” (FDRE) clause requiring that developers provide power to the grid when the grid needs it.

- The term “grid-following” (inverters that mimic AC voltage and frequency) is being changed to “grid-forming” (inverters that provide voltage and frequency support to the AC network) with the new technology of inverter-based renewable generators, allowing for stability of frequency and voltage even when operating in remote microgrids that are weak or where there is no main grid.

Digitizing the Last Mile: AI & IoT

By 2026, the energy gap will have been closed using software as much as it has with physical items. The primary barrier that EPCs are facing when trying to make energy accessible in rural locations is the Maintenance Gap—the cost of dispatching technicians to remote villages to repair individual inverters.

AI-powered predictive maintenance is changing the financial model. Companies can monitor their assets in real-time using IoT sensors. By monitoring their assets in real-time, companies can also determine when they will fail and reduce O&M costs by as much as 20%. The introduction of this digital layer is making it possible for companies to do small-scale rural projects economically—a first.

Today’s 2030 target is now about more than just adding capacity; it’s also about equity. By decentralizing energy generation, through a more resilient grid incorporating energy storage, and providing access to digitally enabled maintenance, India will eliminate the Clean Energy Divide as we move toward a sustainable future.

Tags